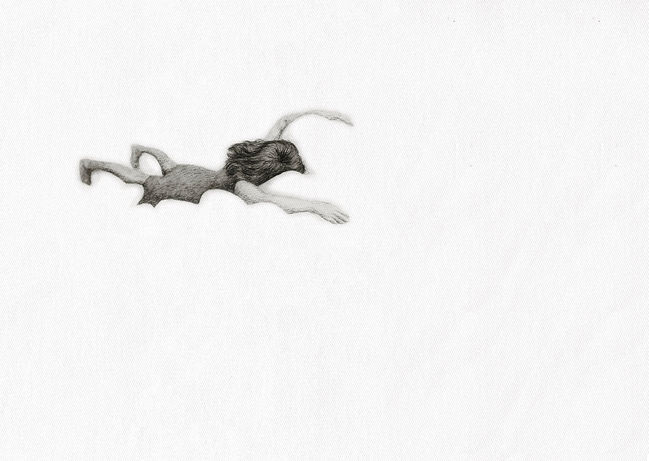

El porvenir es el pasado que vuelve

The future is the past that returns

Dibujo sobre tela. 50 x 70 cm. cada uno. / Drawing on canvas. 50 x 70 cm. each one.

Lo insoportable - The unbearable

Miguel López

Ayacucho, setiembre de 1985. Familiares de las víctimas de la matanza de Accomarca intentan observar el análisis se realizan a los restos de sus parientes asesinados por una patrulla militar. Los cuerpos, sin embargo, no aparecen.

Huánuco, abril de 1994. Dos campesinos de la comunidad de Moyuna trasladan el cadáver de un hombre muerto durante el operativo militar ‘Aries’, en el cual el ejército utilizó helicópteros artilleros contra poblaciones en el margen del Río Huallaga. El cadáver, no obstante, ha desaparecido...

___________

Ayacucho, September of 1985. Relatives of the victims of the Accomarca massacre[1] attempt to observe the analysis made of the remains of their relatives killed by a military patrol. The bodies, however, do not appear.

Huánuco, April 1994. Two peasants from the community of Moyuna move the body of a dead man during the military operation 'Aries', in which the army used artillery helicopters against towns on the banks of the Huallaga River. The corpse, however, has disappeared...

Lima, 1992. Pobladores de Villa El Salvador señalan con el dedo a un presunto miembro de Sendero Luminoso durante una acción cívica organizada por el Ejército. Pero esta persona no está.

Los dibujos de Natalia Revilla auscultan la violencia a través de un trazado silencioso que revisita fotografías del conflicto armado interno entre los años ochenta y noventa. En sus imágenes los elementos ausentes alegorizan la negación y el exterminio del antagonismo social, señalando una tensión irresuelta en la vida del Perú de posguerra: la pregunta por eso que es visible y lo que permanece negado de representación, entre aquello que tiene legitimidad de ser mirado y lo que ha sido marcado como irrepresentable.

La pregunta política por aquello que puede ser o no visto es urgente. Al contrario de lo que el discurso oficial considera, negar el antagonismo no lo hace desaparecer. Estos dibujos aciertan en su voluntad de tocar una exterioridad que permita visualizar al cuerpo social a través de las huellas de su exclusión. Lo que los puros vacíos señalan no es así tan sólo una suma de cuerpos y signos perdidos, sino las formaciones imaginarias que constituyen los límites de lo que aceptamos o reprimimos al momento de percibir la realidad. Y cuyo retorno dice claramente que sea cual fuere el futuro por venir no hay lugar allí para, ni es posible, un total desentendimiento.

Pero estas imágenes son también los síntomas de una falta aún mayor: ponen en escena los fantasmas que el discurso oficial requiere para garantizar el orden y sostener su aparente estabilidad. Lo que descuella en lo que aquí se dibuja –o mejor aún en lo que no se dibuja, en lo que no es posible de ser dibujado–, es un intento nítido de acariciar antagonismos que para diversos grupos y discursos son sinónimo de angustia, y que por ese mismo motivo se les intenta desposeer permanentemente de toda imagen. Allí, intentar darles forma es precisamente una manera de hacer frente a lo insoportable.

___________

Lima, 1992. Villagers from Villa El Salvador point the finger at an alleged Sendero Luminoso member during a civic action organized by the Army. But this person is not there.

The drawings of Natalia Revilla auscultate the violence through a silent contour that revisits photographs of the armed internal conflict of the eighties and nineties. In her images, the absent elements allegorize the negation and extermination of social antagonism, pointing out an unresolved tension in the postwar life of Peru: the question about that that is visible and what remains denied of representation, between that which has the legitimacy to be looked at and what has been marked as unrepresentable.

The political question about what may or may not be seen is urgent. Contrary to what the official discourse considers, denying antagonism does not make it disappear. These drawings succeed in their desire to touch an exteriority that allows visualizing the social body through the traces of its exclusion. What the empty spaces indicate is not so much a sum of lost bodies and signs, but the imaginary formations that constitute the limits of what we accept or repress when we perceive reality. And whose return clearly says that whatever the future has to come, there is no place there for, nor is it possible, a total misunderstanding.

But these images are also the symptoms of an even greater loss: they upstage the ghosts that the official discourse requires to guarantee order and sustain their apparent stability. What stands out in what is drawn here - or better still in what is not drawn, in what is not possible to be drawn - is a clear attempt to caress antagonisms that are for various groups and discourses synonymous of anguish, and for that same reason they are trying to dispossess permanently of all images. There, trying to give them shape is precisely a way of dealing with the unbearable.

____

[1] Accomarca, Ayacucho, Perú. There the Peruvian military massacred unarmed men, women and children. The official number of villagers killed is 69.